Whales in the Great Salt Lake? It’s more likely than you think.

The Salt Lake Tribune newspaper received a letter postmarked Cleveland, Ohio, April 5, 1888, containing a clipping from the Sheffield Enterprise of Alabama and the following request:

“I hadn’t thought of it before, but it is nearly time the lake was full of whales, isn’t it? I would like to know if you think they are ripe. If so I shall spend next winter whaling shoel out of old Salt Lake. Will it be necessary to get a permit from the “Church” to conduct the whaling business? There are thousands of us here in the East who will engage in the business if we can make it profitable. There’s millions in it if there’s no drawbacks. Let us know all particulars. With kind regards, yours, Prescott.”

The Tribune certainly had all particulars and responded with this detailed history:

Just about the time that the Golden Spike was ceremoniously driven at Promontory Summit in 1869, James Whickham, an English professor and expert in the whaling industry, noted that the unchecked commercial whaling industry had decimated sperm whale populations worldwide. While the emerging petroleum industry showed promise in replacing whale oil as a fuel and lighting source, Professor Whickham hoped to tackle the problem by domesticating the sperm whale.

With the Transcontinental Railroad now open, transportation of whale products from the California coast was now fast and fairly cheap, but Whickham saw an opportunity to undercut the California industry by establishing his watery ranch somewhere inland, closer to the Eastern markets. The Great Salt Lake, he felt, was similar enough to the ocean, and the climate of Utah Territory close to that of Southern Australia, that he might be able to pull off the heretofore unattempted feat.

Professor Whickham spent two years hunting a breeding pair that he could capture alive. Considerable expense was made to construct two large portable tanks in which to transport his starting stock. Finally obtaining two whales 35 feet long, the occupied tanks were craned onto the docks of San Francisco in 1873. A special train was chartered on the Central Pacific, each whale occupying its own flatcar, along with fifty tank cars of sea water to replenish their supplies and keep them fresh and happy on the long journey over the Sierra Nevadas into the Great Basin desert.

Arriving from London to meet the train at Corinne, Professor Whickham selected the mouth of the Bear River as his place of business, as the fresh water pouring in from the north diluted the Great Salt Lake’s salinity somewhat. He directed the construction of a wire fence across the mouth, then observed as the tanks were broken open to release the creatures of the deep.

“After a few minutes of inactivity they disported themselves in a lively manner,” the Tribune explained in response to Mr. Prescott, “spouting water as in mid ocean, but as if taking in by instinct or intention the cramped character of their new home, they suddenly made a bee line for deep water, and shot through the wide fence as if it had been made of threads. In twenty minutes they were out of sight and the chagrined Mr. Whickham stood gazing helplessly at the big salt water.”

Whickham, utterly defeated, returned to London in disgrace, but left an agent of his company by the name of Tarpy to see if the whales might be recovered. Six months later they were found. Following the pair in a rowboat for five consecutive days and nights, the agent found that the whales had almost doubled in size and had miraculously produced a large number of young. Whickham’s business took off. Even as whale oil fell out of favor as a lubricant, its value as a lamp fuel was not quickly forgotten, and his whales being located closer to the rabid markets of Chicago or Cleveland did offer him a clear advantage over his competitors who harvested their product on long, dangerous, and expensive sea voyages.

The Central Pacific built a branch down to the lakeshore from Kelton, the western helper terminal on the Promontory Mountains and the closest location to Professor James Whickham’s new processing plant. Soon a fleet of privately-owned freight cars ran back and forth across the Overland Route to markets on all eastern roads, its brightly colored billboard rolling stock spotted anywhere from the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad to the Western & Atlantic. By the time that Prescott inquired of the Tribune as to the profitability of the industry, Professor James Whickham had solidly established himself as one of the successful entrepreneurs of Utah Territory, his “Southern Lights Illuminants” brand finding ready buyers both in the Wasatch homesteads and in the great municipalities of the industrial east.

Sources

“Very Like a Whale,” Jefferson County Sentinel (Boulder, Montana) Friday 4 May 1888.

Utah Enquirer (Provo, Utah) 24 June 1890

“Whale of a Salty Tale Swims Through Pages of Old Paper,” Deseret News 3 October 1995.

Weis, Meghan. The Beehive Archive: A Whale of a Tale from Early SLC Newspapers. The Herald Journal 31 January 2022.

The Southeastern connection

Further details about Professor James Whickham’s oil empire were recently uncovered by the equivocal railroad author Eddie Sand (no relation to another, more famous railroad author of the same name) while researching the Western & Atlantic’s post-Civil War operations:

“British scientist and entrepreneur James Wickham arrived in the United States from London in 1866, lured by the promise of fortune in the untamed wilderness. A well-educated and inventive man, Wickham set out to prospect for Unobtainium in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. He established himself along the Pemigewasset River, where he developed a chemical process to amalgamate ore. However, his ambitions were short-lived. Less than a year into his venture, a territorial ‘wolfman’ with a rival mining claim drove him out, forcing him to seek fortune elsewhere.

“By 1868, Wickham had a dream—quite literally. He recorded in his diary a vivid vision in which spirits guided him westward, urging him to follow a pod of whales. The imagery he wrote about was striking: massive whales swimming gracefully in the hot air above the Great Basin, their slick bodies shimmering under a desert sun. Convinced that the vision was a sign of his destiny, Wickham set forth on an audacious plan.

“During this era, whales were primarily hunted for their blubber, which was processed into oil for lamps, lubricants, soaps, and even margarine. Baleen, or whalebone, was equally valuable, used in corsets, umbrellas, and buggy whips. Wickham reasoned that if he could capture and transport a breeding pair of whales inland, he could create a self-sustaining population. Thus eliminating the dangers of maritime whaling while ensuring a steady oil supply.

“Operations expanded rapidly. Company offices sprang up on both coasts, and a fleet of railcars was commissioned to transport whale oil across the country. The cars, as described by contemporary observers, were of various designs, making consistent descriptions difficult.

“For decades, it was believed—based on the 1950s research of railroad historian Lathrop Beebe—that these cars were painted black and green. However, a recently uncovered Sacramento Bee newspaper article suggested that at least some of the fleet was painted in Prussian blue. [Editor’s note: Mr. Beebe was not entirely in error; contemporary descriptions from the Utah whalers indicate that many of the cars were in fact painted a rich green with black asphaltum on the ironwork to protect against the harsh salty atmosphere around the Great Salt Lake. The debate over verdant shades continues in spirit today among Colorado narrow gaugers.]

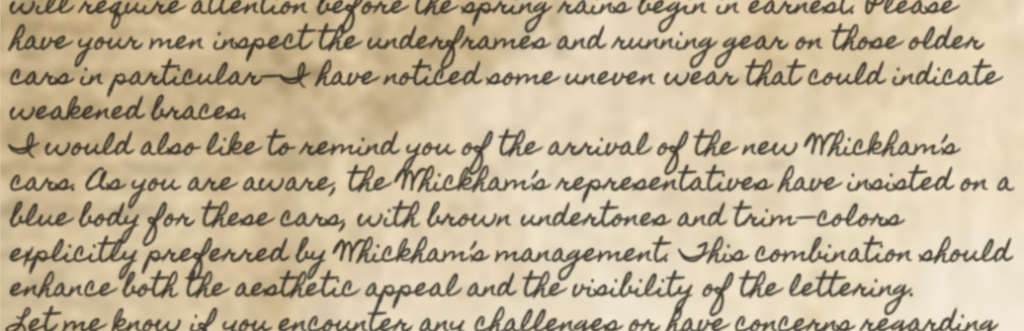

“Additional evidence surfaced in a series of letters written by Martin H. Dooley, the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Western & Atlantic Railroad. This extensive correspondence details the technical aspects of the W&ARR’s freight rolling stock, offering invaluable insight into the railroad’s equipment and design choices. In one particular letter dated January of 1885, Dooley makes a brief yet intriguing reference to the upcoming arrival of a “Whickhem’s car,” (Seemingly misspelled. One wonders if this was one of the first times he had heard of the company) specifying that it should painted blue. He further describes brown undertones and trim, a detail that challenges the previously held assumption that the car’s trim was black. The snippet of that letter is included here.

“Despite its unexpected success, the company’s fate was sealed by the inevitable. Overhunting of the whales led to a rapid decline in the population, and with the rise of kerosene and petroleum-based alternatives, demand for whale oil dwindled by the turn of the 20th century. The once-thriving enterprise faded into obscurity. Yet, legends persist. Some claim that on rare occasions, a whale can still be spotted breaching in the Great Salt Lake, a phantom of Wickham’s grand vision. The Superior Great Salt Lake Whale Oil Co. somehow managed to cling to existence for over a century—until it succumbed to economic collapse during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.”

[Editor’s note: facing severe competition from Continental Oil Company which was established in November 1875 in nearby Ogden, Utah, Whickham’s company shifted to prospecting the petroleum tar seeps that emerge from the shores of the north side of the Great Salt Lake, but to marginal success. Leasing its claims to these oil sources was enough to allow the company to scrape by for the past century with a single agent.]

The truth

During the 2019 anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, attention returned to this odd entry in Utah’s old news. Since then many documentaries and exhibitions have emerged from the limited newspaper clippings exposing the whaling industry of old Utah Territory. Inspired by the historical sources, we designed a speculative decal set as one of our earliest products to bring Professor James Whickham’s whale oil to your layout. The model that is used in the product photography is a modified HO scale Model Die Casting 36′ boxcar that was painted green simply to stand out from trains of boxcar red and mineral brown. You can order the decals from 3DpTrain at this link.

The 1888 and 1890 articles cited above really were printed by actual newspapers. Our ancestors did in fact pay ten or so cents to read tall tales that would put Old Abe Lincoln’s yarn spinning to shame amid their daily dose of yellow journalism.

In spite of years of sleuthing no historian has cracked the case of where this whale of a tale originated. Prescott’s 1888 letter to the Tribune appears to be the earliest mention that can be found in the national press, reprinted in various papers around the country. An observant reader will note that the tone of the letter is solidly tongue-in-cheek, as is the response. Utah’s newspapers found it quite hilarious and revived the story a handful of times through the 19th century, each time tightening the deadpan tone until it appeared no different from the daily news. The Utah Enquirer finally admitted that they reveled in pranking eastern newspapers into repeating an obviously implausible joke. The Great Salt Lake whaling industry was eventually mostly forgotten, vague traces living on in the urban legend that Utah state code criminalizes whaling expeditions on the Great Salt Lake.

It turned out that the whimsical nature of this decal set led it to popularity, becoming one of Great Basin Car Shops’ best selling products. The lore behind Whickham Whale Oil grew, with customers writing their own additions to the “historiography.” The Western & Atlantic connection was written by a friend of Great Basin Car Shops to explain the unusual concentration of Whickham Whale Oil boxcar models in their region of the country and why they deviated from the established green color. Special thanks for sharing photos of their creative work.

The final paragraph of the Salt Lake Tribune’s 1888 response to Mr. Prescott wraps it all up neater than a gift under the Christmas tree:

“The younger whales will not be ready for harpooning before year after next but the liar who first started the cannard ought to be harpooned at once.”

Leave a comment